For a Sector that requires one of the largest sustained funding requirements in decades, financing for clean energy investments in India has had a rocky ride. The three year lock-in for developers is the most recent obstacle.

Bankability. That’s a word that is highlighted proudly across the solar chain, and whose value can never be underestimated. Be if the developer who has to have the cash and balance sheet strength to raise funds, or the many vendors, from the modules to the inverters who need to have the credibility to assure financiers that using their products is indeed the right move. Bankability, or simply, access to finance or even qualifying for financial support has become a critical issue for the sector today. Interestingly, just a little while ago, we witnessed the sight of the National Solar Energy federation of India (NSEFI) protesting about NTPC’s refusal to waive off EMD (Earnest Money deposits) for small and medium enterprises, when bidding for their solar tenders of close to 923 MW.

When we mentioned this to one of the many developers we spoke to, one of the larger ones shrugged, and added that its not as if they have it easy too. “One of the most irritating aspects of the bidding process that has emerged with time is the struggle to get back your EMD’s, after the auction is over”. He claimed that not only do they face regular delays there, EMD’s, along with non-refundable processing fees, are a major reason for even some larger developers staying away from multiple bids simultaneously. With EMD’s ranging between Rs 6 lakhs to Rs 20 lakhs per MW on most SECI and NTPC projects, the amounts can add up, for larger bids. For smaller firms looking for exemptions under the MSME policy of the government, NTPC’s stubborn refusal to exempt them adds to the challenge. In fact, when it comes to money, developers blame that everything they want has to be paid for upfront, but their most critical cash flows, the payments from Discoms, are breaking new records in payment delays every month. Not the best way to nurture an emerging sector, surely?

But let’s move on to the large financing challenge. Globally, new clean energy financing for emerging markets slipped to USD 133 billion in 2018, against USD 169 billion in 2017. India too contributed to this global contraction in clean energy investments by declining USD 2.4 billion in 2018 as compared to the previous year, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance’s (BNEF) 2019 report on emerging markets.

But let’s move on to the large financing challenge. Globally, new clean energy financing for emerging markets slipped to USD 133 billion in 2018, against USD 169 billion in 2017. India too contributed to this global contraction in clean energy investments by declining USD 2.4 billion in 2018 as compared to the previous year, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance’s (BNEF) 2019 report on emerging markets.

On Asian nation’s individual performance, Rohit Gadre, Analyst India BloombergNEF commented “India was the world’s largest renewables auction market in 2018. The competitive and transparent auctions have attracted foreign investment and led to lower tariffs.”

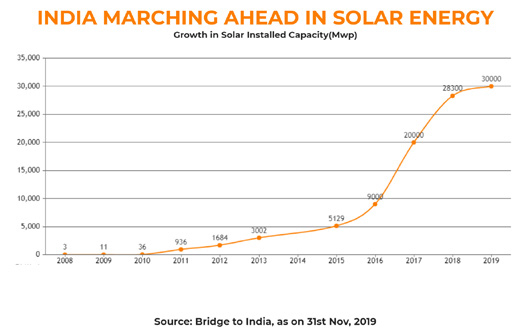

Something clearly didn’t work, as solar installations crashed between 2017 and 2019. Also, 2019 was particularly disappointing with even the reduced target of 9 GW capacity addition missed with installations declined by almost 35 percent from the same period in 2018. In 2018, it had recorded 15 percent decline over 2017. Worse, even rooftop solar which now has simply impossible target of 40 GW by 2022, dropped sharply on its small base.

2020 brings fresh challenges

The World Bank has recently trimmed India’s growth for FY 2020 to 5 percent from its earlier 6 percent projection, which is lowest in past 11 years. Growth is expected to recover slightly in the next fiscal year to 5.8 percent. The main reason behind the downgrade is lingering weakness in credit from non-banking financial companies (NBFCs).

On the renewable energy front, investments across the sector stalled throughout 2019 on the back of inability of Discoms (power distribution companies) to make payments. The move was a warning light to global investors about the lack of sanctity of contracts, drawing global criticism to the country. These worries found reflection in the negative outlook given by ratings agencies like CARE Ratings to many solar power generators with Discoms as clients in states like Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. This further added to the pain of the developers as they are facing steep difficulty in servicing their debt.

Record low tariffs have also had lenders taking a much harder look at proposals, in terms of long term viability.

Efforts from the government to ease the situation – be it offering state governments with concessional loans from its state-owned lenders such as Power Finance Corporation (PFC), Rural Electrification Corporation (REC) and Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA), missing to open LC’s now before committing to power off take, and so on, have largely failed to make the sort of impact envisaged.

On top of all these issues which renewable energy developers were grappling with, came the power ministry amendments in July 2019 to the guidelines for tariff based competitive bidding process for the procurement of power from grid connected solar photovoltaic (PV) power projects. With the new amendment, solar project developers are now required to maintain a controlling stake of 51 percent in the special purpose vehicle (SPV) or the project company executing the power purchase agreement (PPA) for 3 years from the commercial operation date (COD). Earlier, this period of maintaining 51 percent shareholding in the SPV or project company was for a period of 1 year from the COD.

Speaking on the government’s motive behind this move, Rananjay Singh, Head – Business Development at Gensol Engineering, an arm of Gensol Group that offers an EPC & solar advisory services, was of the view that “there are plants which were developed with low grade equipment especially modules. The generation from these plants has dropped drastically and defeats the purpose of having major chunk of power from renewable energy in the country. There have been cases wherein the developer had sold the plant post lock-in restrictions and the generation of the plant has degraded drastically.

Thus, to discourage such intentions and avoid assets with lower grade modules, inverters and other equipment, the lock-in is revised, as the developer has to maintain the plant for 3 years and all the flaws will surface during this period. This move may control the quality of the assets and may serve as a step to save Nations’ interest.”

On this another major developer, Azure Power’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO), Ranjit Gupta says “the intent of government behind this move is to protect the industry from investors looking at short-term gains. And increase the solar power project quality with the use of better quality modules as poor quality modules will show degradation within three years.”

However Ranjit Gupta has a caveat to add “there are various ways to ensure quality of modules like photovoltaic (PV) module qualification and safety standards, which are already being factored in tenders. Also, looking at the project sizes, all independent power producers are focused long term companies who will not compromise on quality modules as it would impact their generation and valuation where again, there are penalties in the PPA as a deterrent. Most importantly, in case of new financing after a year, the new investors will do its detailed due diligence for the project, therefore there is no reason to believe that the developer will compromise on the quality of the project.”

Offering a contrarian view on 3-year lock-in period P. Vinay Kumar, Founder and CEO of Varp Power, owner and operator of solar rooftop/open access developments, says “it will have the unfortunate impact of slowing down secondary sale of assets and will impede the recycling of capital for developers/ IPPs. It may worsen an already stretched liquidity position and can impact their under-construction solar pipeline indirectly.”

Kumar further suggested that “a better way of achieving the asset quality objectives will be to have a robust mechanism of enforcing quality standards for modules, BoS components and equip agencies like BIS with more teeth.”

Sanjeev Aggarwal, Managing Director & CEO of Amplus Solar, now a part of the Malaysia-based Petronas (Petroliam Nasional Berhad) Group and distributed energy provider to C&I customers, also seemed to understand, yet have his doubts on the move.

Aggarwal remained cautious about short term equity investment for developers and said “with doors being closed for short term equity investors due to the lock in and with little or no interest expected from the long-term investors with the lowest risk appetite due to construction risk, the long-term impact would be that fewer new investors will enter the market. It will just be the existing large developers (who take the risk of construction and hold the project for 25 years) participating in new bids and building their portfolio size.”

Besides, other industry stakeholders Manoj Gupta, VP-Solar and Waste to Energy Business, Fortum India, an Indian arm of Finnish state-owned energy company Fortum, has no doubts on the relevance of the move, and said that “this is not a welcome move as per my perspective and I don’t know the government’s intention behind this. As an industry, we always oppose any kind of lock-in period for shareholding. It was initially started under Gujarat Solar Policy in 2010 and lots of developers couldn’t attract any foreign investment due to this lock-in. In fact, foreign investment in India was delayed due to 5 years lock-in under Gujarat solar policy. Under National Solar Mission program, the lock-in period of 1 year was a good move by the Centre but from a developer’s perspective we do not want any kind of restrictions in lock-in so that in case of any fund constraint, there is sufficient freedom for the developer to bring the investor to any extent. It will help in commissioning of all those projects on time that have fund constraints.”

Manoj Gupta also pointed to the performance bank guarantee clause and said that “as far as government is concerned, at the time of signing of the PPA, developers must submit the performance bank guarantee for timely commissioning of the project which is already a sword on his neck.”

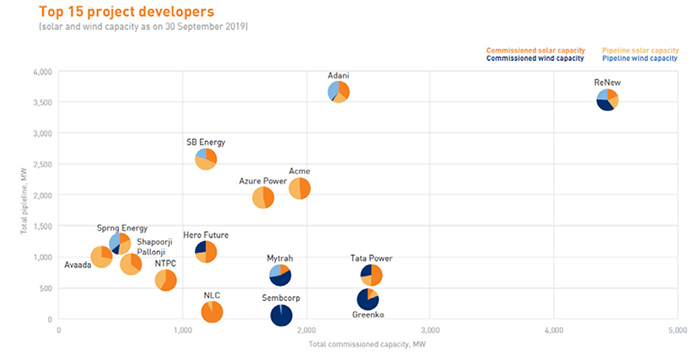

So the clear takeaway seems to be – advantage large developers. It’s not an idle claim, if you consider the roster of India’s top developers today. At least four of the biggest, Tata Power, Adani Green Energy (part of the Adani Group), NTPC and NLC, are large legacy firms with interests in thermal and coal. While the rest of the top 15 are dominated by firms with an outstanding ability to raise funding (ReNew Power, Avaada Energy) or backing from private equity financing. It is the firms which have neither of these attributes that are struggling to big aggressively today, be it ACME Solar which bid low to win but is struggling with payment issues, or even SB Energy, reportedly under some pressure due to the travails at its parent firm, Softbank. Renew Power for instance, clearly doesn’t have to worry about such issues, with over USD 1 billion in fund raises during 2019 itself, from a USD 300 million rights issue to a USD 375 million green bonds issue and a debt issuance of another USD 300 million.

On the other side, for meeting the government’s objective of ensuring a better quality of panels and equipment being used, Animesh Damani, Managing Partner of Artha Energy Resources, an advisory firm that is focused in attracting and bringing new investment into the power generation industry in India, adds that “the move is fundamentally flawed. Simply increasing the lock-in period from one to three years does not mean better quality of panels or equipment will be used. Most solar projects do not witness high degradation in first 5 years. It is after the 5th year that degradation of panels comes to the fore. Hence, I don’t think the objective of ensuring a better quality of panels and equipment will be met with this change.”

For the long term impact, Mohua Mukherjee, Energy and Climate Finance Expert; Program Ambassador Pro-Bono at International Solar Alliance (ISA), clearly stated “I don’t think this objective will be met on a large scale. Some investors who would be willing to commit their funds to a project for a maximum of 18 or 24 months, but not longer, will now be absent from the pool of solar project funders. The long term impact could be to drive DOWN investment instead of helping the sector.”

Thus, looking at the broader fund raising numbers too, one can see that the move risks concentrating the industry further into a premier club of large developers, reducing overall competition in the long term.

Azure Power’s Ranjit Gupta’s words simply point to this risk, “we all need to appreciate that there are different types of investors who have different risk appetite and project return expectations. Most of the renewable energy firms work with the investors who are comfortable with the risks associated with a greenfield project but since capital is a limited resource, they need to have an ability to churn their existing portfolio with a premium for operational portfolio and redeploy the proceeds towards implementation of incremental capacity. The ability to churn the portfolio at premium without significant time constraints, allow a developer to aggressively participate in the bids. Any move that restricts this circulation of capital by greenfield investors will keep them from bidding, which will in-turn reduce competitive intensity in auctions, thereby leading to an increase in consumer tariffs and decrease in sector efficiency.”

On another category of brownfield investors Ranjit Gupta added “they like to invest for a long term, through structures like portfolio buyout, InvIT etc, which comprises of a pool of projects. These investors have not only played a critical role of ‘freeing up the risk capital’ that is provided by greenfield investors and have meaningfully contributed to the FDI over last few years.”

Rananjay Singh points out that “over the past 8 years, a bulk of greenfield investment in India has been made by Private Equity type investors through their investments in platform companies. Further, there are provisions existing in the bidding documents (like bid/ performance bonds and net worth requirements) which hereby ensures that only serious investors participate in the India RE sector. Now, if we calculate for an aggregate time duration for which the money remained blocked in a particular project – it is not just three years, it will go up to five years. 2 years for construction plus 3 years Lock-in.”

In fact Singh suggested that “the government has to consider, are they really achieving target requirement by such changes or not? With the help of longevity of tenure, government shall be only able to demonstrate stability in Owner ship change.”

So, in such a scenario, where does the sector stand? Ranjit Gupta reckons that “the underlying fundamentals of Indian solar sector is very strong, therefore, the sector will continue to attract investments but it may reduce the spectrum of investors that can participate in the various stages of the sector’s life cycle, thereby impacting the flow of capital, and reducing total investment.”

However, Ranjit Gupta also expressed a worry that “it may also increase the return expectation of an early stage investor, who will see their investment as compulsorily locked for around 4-5 years (including construction period), irrespective of performance of the assets.”

On foreign investment in the solar sector, for P. Vinay Kumar, it seems to be a case of a step backward for every step forward. “We have a very vibrant secondary market for solar assets now with significant interest from foreign investors. New structures like Renewable energy Investment Ttrusts (INViTs) are built on the premise that solar assets can be flipped into such vehicles offering the much needed liquidity to the developers who can recycle capital and release it to build new plants.” But now, Kumar adds, “increasing the equity lock-in will impair the ease and efficacy of these investment vehicles in accessing solar assets. The existing equity lock-in restrictions of CoD + 1 year itself poses a concern, when the developer wants to sell the assets within a year of commercial operation date. Investors often resort to artificial and inventive structuring to skirt this equity lock-in condition in a seemingly compliant manner. This need for inventive structuring will only exacerbate with the prolonged equity lock-in period increasing the risk of transactions.”

Sanjeev Aggarwal stresses the need to not discriminate too much between investors, with each having a key role to play. “In order to ensure the sustainable and robust growth of this sector, it is necessary to have a balance of long-term and short term equity investors, both of whom have a different risk appetite.” As Manoj Gupta says “arranging non-recourse finance was always difficult for renewable energy projects. It was never an easy cake-walk. However, the kind of issues this industry is struggling now a days such as reopening of signed PPA, late payment, safeguard duty introduction, change in GST rate etc. have almost dried the financing for the Indian Solar industry. Private equity investment or bridge financing was somehow being used to fill this massive gap. The introduction of 3 years lock-in will make arrangement of equity financing even more difficult”.

It’s a contention Ranjit Gupta too agrees with, adding that “it has been a difficult task for developers to raise equity as well as debt in a market already facing a liquidity crunch. While this lock-in might not significantly affect debt by reducing exit flexibility, it may affect equity availability options in the market.”

If seeking better quality and commitment was the aim, were better options available?

In Manoj Gupta’s view “the better option was to remove the one-year lock-in and give more freedom to the investor and developer to raise their equity even during the construction of the project.”

It’s a view that finds some support from Mohua Mukherjee too, with her advocation to “leave things as they are, and let lenders and developers deal with each other. There should be no administrative interference.” Animesh Damani further suggested that “government should clearly define the quality standards for the panels and equipments being used.”

“Along with setting high standards of quality for equipment, government could have set up enhanced checks and stricter monitoring of these projects in the 1 year of lock-in. This could have ensured that more marketable and sustainable solar projects are developed in the country,” believes Sanjeev Aggarwal of Amplus Solar.

It’s a view that finds supporters across the board. In fact, it’s a common sense view, when you think about it. Ensure tight entry norms, and after that, allow the market to work. But like most cases where the government has multiple interests to balance, in this case, the pressure to drive down costs, yet maintain quality and ensure growth too, the government has simply struggled to arrive at a clear vision to allow the sector unfettered clarity for even a 3 year lock-in period. That, for India to meet its 2022, 2030 and even further vision, needs to change, and change fast. February 1, 2020, when the budget is being presented with high expectations of more ease of doing business, would be a great day to start.